| |

||||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||

| 4 | education | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | research | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | outreach | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | dialogue | |||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

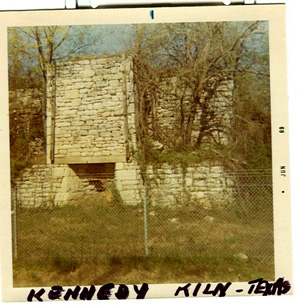

Archaeology of the Irish Diaspora in Texas, Maryland.

|

Texas, in present day Baltimore County, is an unincorporated village located 12 miles north of Baltimore City. The site is located in a densely populated and heavily commercial and industrial corridor of Baltimore County (MAAR Associates 1992: I-12-I 13). It is situated in an area called the Limestone Valley because of the rich vein of limestone that is still quarried today. Quarrying was a small-scale production. The completion of the Baltimore and Susquehanna Railroad in 1832 allowed for better and more efficient means of transporting the limestone and finished marble, which was noted for its exceptional high quality (Brooks et. al. 1979). As a result, its production increased exponentially.

The village of Texas emerged as an Irish community as early as 1847. The increased quarry activities created a demand for skilled and unskilled laborers. This coincided with the arrival of thousands of Irish immigrants to Baltimore City seeking to escape the horrors of the Great Hunger, also known as the Potato Famine. Based on the U.S. Census figures the settlement of Texas began by 1847 and an established Irish enclave by 1860. The limestone quarried by the Irish was used for building projects such as the Washington Monuments in Washington D.C. and Baltimore City, the State House in Annapolis, the porticoes of the Senate and House wings of the Capitol in Washington D.C., and as far as away as St. Patrick’s Church in New York City (Anderson 1982).

|

Drawing from the records of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, built by the Texas Irish immigrants in 1852, and Church’s cemetery headstones, the Irish inhabitants hailed from the west of Ireland (Smith 1927). The western provinces were most affected by the failure of the potato, as it was for most rural poor their only means of income and subsistence. The headstones being a unique, informative, and intimate historical resource reveal each individual’s parish and townland in Ireland. It is evident that more than half of the population of Texas was made up of individuals from the townland of Ballykilcline in County Roscommon. This represents a unique archaeological context as extensive archaeological work on pre-Famine cabins has been conducted in townland of Ballykilcline (Orser and Hull 1998; Orser et. al. 2000). The comparisons of material in Ireland and Texas will provide for much interesting studies in material changes reflecting shifts in cultural and social behaviors. The work will also bring attention to and study of community formation of diverse Irish groups. Not all of the inhabitants were from Ballykilcline. Several Irish households were from various rural regions of Counties Cork, Mayo, Kerry, and Limerick and each area had distinct cultural traditions. Regardless, all inhabitants were part of the larger history of the Irish Diaspora. The work proposed here will be the first archaeological survey of an Irish immigrant village in the United States.

The vision for this

anthropological-based archaeological research is to locate, collect, and

interpret the historical, ethnographic, and material context of the Irish

of Baltimore County through a site specific study of a mid-19th century

Irish immigrant quarry town known as Texas. Little is known, historically,

of the daily lives of “quarry-Irish” in Texas, Maryland. Historians of

Irish America have only hypothesized the experiences of Irish immigrants

being uprooted from their homeland and transplanted in new social and

cultural landscapes (Kenny 2000). Maryland has a rich Irish and Irish-American

history beginning with the 17th century Irish-Catholic Carroll family

and presently Maryland’s Irish-American governor, Martin O’Malley. Irish

immigrants have come to, and made an impact on the formation of, Maryland.

Missing from the historical narrative of immigrants and laborers, however,

is a study of their daily lives. The importance of archaeology to the

humanities rests with it being a multidisciplinary social science focusing

on material and social relations within and between different economic

and ethnic collectives (Leone 2005; Mullins 1999; Orser 1996; 2008; Saitta

2007; Shackel 1996). It is the actions of the collective, formed through

shared social interests, experiences, cultures, and ideologies, that structure

the practice of day to day life and is reflected in archaeologically-recovered

material culture (McGuire 2008: 45). Archaeology is not an independent

line of inquiry from other disciplines. The advantage of the discipline

rests with its abilities to track different or hidden aspects of the historical

process, especially at the point of mismatch between objects and documents

where artifacts can illuminate social processes, identity formation, and

resistance or incorporation into the larger society (Leone 2005).

The archaeology of

Texas, in conjunction with the collection of ethnographic, social, and

economic histories, will provide the necessary and important data towards

understanding the immigrant presence and everyday life not evident by

the historical record alone. The data recovered archaeologically will

be put on the regional, national, and international stage of the Irish

Diaspora and will bolster and create new interpretations concerning the

material manifestations of collective identities. The research is framed

by questions such as what impacts did the Famine, eviction, and transportation

have on rural Irish cultural practices? What kind of social and material

life did Irish evictees have after settling in Texas and how was it affected

by their traumatic Irish past? What cultural and material practices were

adopted in the United States? How does this compare to other Irish immigrant

experiences throughout the United States?

The overall importance of this proposed research is its continuing contribution

to the scholarship of immigrant life histories and community formation,

the transformation of collective identities, labor history and working

class identities, and the changing material conditions and experiences

of everyday life of immigrant and first and second generation American

laborers. Furthermore, the knowledge gained through this survey will shine

a much needed light on preservation of historic sites. In 1982 the area

of Texas village was nominated to be listed on the Maryland Historical

Trust’s register as a historical district because it made significant

contributions to the historical, architectural, industrial, educational,

and religious fabric of Baltimore County, as the village embodies the

characteristics of a mid-19th century Irish-Catholic working class community

that developed into one of the most important centers of Maryland’s quarrying

and burning of limestone (Anderson 1982). Since the nomination survey,

a good portion of that history and with it the archaeological record has

been slowly eroded away by suburban sprawl and commercial development.

It is of extreme importance that a long-term, in-depth, and well published

community-based archaeological, historical, and ethnographic research

program be conducted that highlights and preserves the village’s significance

to local, national, and international history.

The research design is structured to contribute to the knowledge of and gain support from the local and descendent community. The project will be a collaborative community-driven effort. The main community group is the Ballykilcline Society (www.ballykilcline.com). The group was formed in 1997 and is a somewhat virtual community made up of families and individuals across the United States and Canada who share an interest in and study of their familial connections to Ballykilcline in Ireland as a way of understanding their place and experiences in the United States (Dunn 2008). Texas, Maryland is one of the unique places in the group’s history. At this time we are in the process of creating a new group, “The Friends of Texas, Maryland”, which will incorporate all interested community members in Baltimore County, and especially descendents of Texas.

The project is teaching and community oriented. The philosophy of the project is to be inclusive and acknowledge the various interest groups and stakeholders. More importantly, the results will be disseminated in numerous and diverse forums. The professional audience will be historians, historical geographers, anthropologists, preservationists, material cultural specialists, and archaeologists who will all be able to draw various threads of evidence to be incorporated into their own diverse studies of the humanities. The scope of the project and the study of the material remains will be geared towards answering some of the community’s questions concerning experiences, living conditions, and the material lives of their ancestors, and concerns about preserving their families history. Archaeology or at least the materials recovered from excavations will provide the intimate and real connection to their families past.

References

Anderson, Marion. 1982. “Texas, Maryland, Historic District Nomination.”

Maryland Historical Trust

State Historic Sites and Inventory Form

Brooks, Neal A.,

Eric G. Rockel, and Ted M. Payne. 1979. A History of Baltimore County.

Friends of

Towson Library, Inc. Towson, MD.

Dunn, Mary Lee. 2008.

Ballykilcline Rising: From Famine to Immigrant America. University of

Massachusetts Press. Amherst.

Kenny, Kevin. 2000. The American Irish: A History. Longman, NY.

Leone, Mark P. The

Archaeology of Liberty in an American Capital: Excavating Annapolis.

University of California Press, Berkeley.

McGuire, Randall.

2008. Archaeology as Political Action. University of California Press,

Berkeley.

Mullins, Paul. 1999.

Race and Affluence: An Archaeaology of African America and Consumer Culture.

Springer, New York.

Orser, Charles E. 1996. A Historical Archaeology of the Modern World. Plenum Press, New York.

Orser Charles E.

2008. Historical Archaeology as Modern-World Archaeology in Argentina.

International Journal of Historical Archaeology 12: 181-194.

Orser, Charles E., Jr. and Katherine L. Hull. 1998. A Report of Investigations for Archaeological Research at Mulliviltrin, County Roscommon, Ireland: A Tenant Village Destroyed During the Mass Evictions of 1847. Centre for the Study of Rural Ireland, Normal, IL.

Orser, Charles, Jr., David S. Ryder, and Jessica Levon. 2000. A Report of Investigations for the Second Season of Archaeological Research at Ballykilcline Townland, Kilglass Parish, County Roscommon, Ireland. Illinois States University, Normal, IL.

Saitta, Dean. 2007. The Archaeology of Collective Action. University of Florida Press, Gainsville.

Shackel, Paul. 1996.

Culture Change and the New Technology: An Archaeology of the Early American

Industrial Era. Springer, New York.

Smith, Albert E.

1927. The Diamond Jubilee of Saint Joseph’s Parish, Texas, Maryland (1852-1927).

St.

Joseph’s Church, Baltimore.

| © 2003-2005 University of Maryland |

|